Directors Share Insights into the Life and Legacy of the Enigmatic Musician

By Dolores Quintana

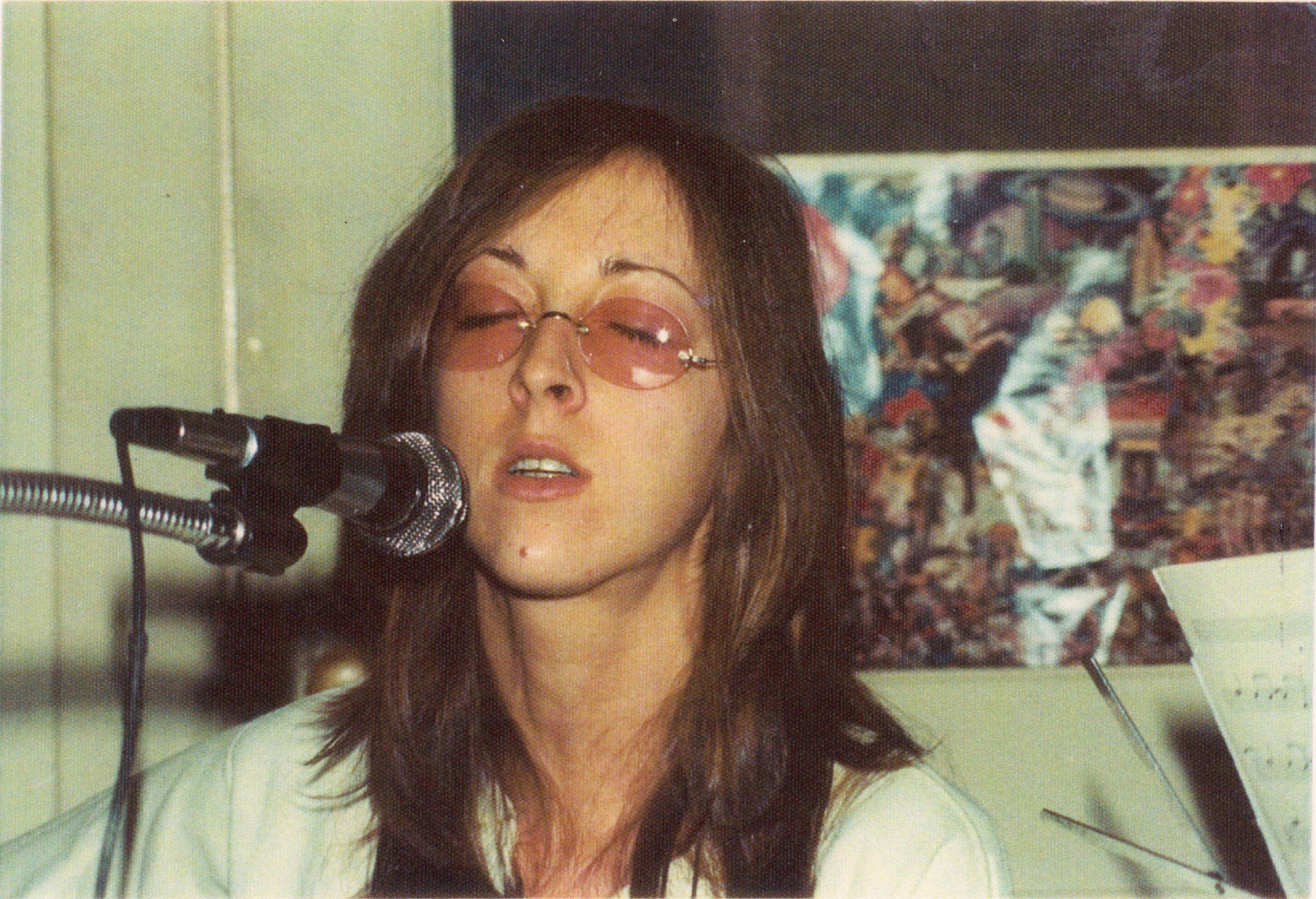

Have you ever heard of Judee Sill? If you haven’t, you should, and now you have the chance to learn about her life and her music with the release of the documentary Lost Angel: The Genius of Judee Sill opens this week in theaters, on digital, and on-demand, Apple, Amazon, Vudu, and other major platforms, in the US and Canada on April 12.

The film is the never-before-told story of folk-rock icon Judee Sill, who, in just two years, went from living in a car to appearing on the cover of Rolling Stone. The documentary charts her troubled adolescence through her meteoric rise in the music world and her early tragic death. It features Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, David Crosby, Graham Nash, Fleet Foxes, David Geffen, JD Souther, Big Thief, Weyes Blood, Tim Page, and more. Executive Producers include Maya Hawke and author Cheryl Strayed.

I spoke with the film’s directors, Andy Brown and Brian Lindstrom, about Judee Sill, making the film, and the magic of this extraordinary woman and musician who is undefeated by time and her own death. She wrought magical and timeless music that still moves people to this day.

You can view the trailer here:

Dolores Quintana: Brian and Andy, I guess I should start at the beginning. What was it about Judee Sill and her life that moved you so much that you felt you needed to make a film about her?

Andy Brown: Well, I, for me, I mean, I had heard about Judee from a musician named Andy Partridge, the English musician who founded XTC, in an interview, but it was really the video of her from The Old Grey Whistle Test, of her singing her song, The Kiss. It really blew me away. Maybe a year later, I showed it to Brian, figuring it would have the same effect on him because I knew him. That was what started us talking about doing something and that was over eleven years ago now.

Brian Lindstrom: Just the more we got into her music, it changes your life. You can’t not listen to it, and then we started to really try to understand who she was as a person. We did as much research as we could. It was this incredible juxtaposition of this ethereal, hymn-like music, and I mean that in the best sense of the word. Not like any kind of a specific religion, but just more spiritual.

That seemed, at first glance, to really be at odds with some of the facts of her life. She was an armed robber, had a history of addiction, and all those things. But as we really got into it and understood her more, in her own words, we understood that so much of this was just a reaction to her childhood trauma. So many of the hard decisions that she made, like the armed robbery. She said she was doing those things just to feel something,

Andy Brown: That included [the fact] that she probably had a predisposition for addiction. But that childhood trauma certainly was a trigger for getting hooked on drugs fairly early on, in her mid-20s. She got hooked on heroin for the first time, which she kicked in prison in 1968 after being busted for forgery when she was writing bad checks to support a heroin habit and doing sex work, too.

She said to herself, while kicking heroin in prison, that if I can do this, I can do anything. This was in 1968, and she decided she wanted to be a singer-songwriter, so she got a treble clef tattoo on her arm in prison. Four years later, she was on the cover of Rolling Stone. What happened afterward is sad and tragic in a lot of ways, but it was a meteoric rise. It was really quite impressive.

Brian Lindstrom: In her diary, she wrote, “The lower down you go to get your momentum, the higher up it will propel you.”

Dolores Quintana: I think a lot of people put judgments, particularly on musicians, on people who have drug and alcohol problems, and particularly if they’re women; I think it is a heavier judgment.

Andy Brown: In those days, especially, yes.

Dolores Quintana: I was wondering because I thought about it in regard to other musicians. Do you think, from what you’ve learned about Judee Sill, that maybe part of what people call a self-destructive urge in someone like this might have something to do with the fact that they feel they’re not being heard as people and musicians?

Andy Brown: Are you talking about when she first started using drugs or after her problems with losing her record deal?

Dolores Quintana: I think it would be more afterward, but it might figure into most of her life.

Andy Brown: I think you’re right. I think that it was very painful for her. There were several reasons why she got back on drugs, but one of them would certainly be the psychic pain she experienced from the lack of interest in this beautiful record, Heart Food, that she made. I think that it was as hard to deal with any pain from back surgery she had, and so on, if not more so.

Dolores Quintana: It just occurred to me that everybody loves to call musicians, in particular, self-destructive as if they don’t want to be successful. The whole reason why they’re musicians is because they have something inside them that they want to communicate to everyone else.

Andy Brown: Adrianne Lenker says something about how the rejection and pain of the lack of response for those records would have reminded her of the rejection she felt from her childhood. It would have opened up that psychic wound in a profound way. I absolutely think that’s true, and it contributed to her seeking to numb herself in some way.

Brian Lindstrom: I think it’s easy to look at Judee and make judgments like she’s self-destructive or whatever. But I think it’s also instructive to look at Judee through another lens, which is how self-preserving she is. She found this music, created this music, and devoted herself to it. In many ways, it saved herself up to a certain point. I think she felt it could save others. If you have that feeling about your work, imagine what it feels like then when it doesn’t reach the audience that you think it deserves. It’s like a double disappointment.

Dolores Quintana: Tell me a little bit about the process of putting this film together and what it meant to you.

Brian Lindstrom: Well, it’s been such a rewarding journey to live with Judy and her music for all these years. It’s been a life-changing experience for both Andy and myself. I hope I can speak for Andy in that regard.

Andy Brown: Oh, yeah. I thank Judee every day. I really do. She’s the most inspiring person. I’ve never met her, but I’ve ever sort of felt like I’ve known, and I do feel like I know. It’s very bittersweet, all of this, because she’d be so thrilled to know that now people are being touched by her music in the way that she had hoped. Of course, she can’t experience it. But, if anybody is existing on some metaphysical plane, it’s her. So you know, maybe, I don’t know.

Dolores Quintana: Honestly, until we get there, we have no idea.

Andy Brown: There you go.

Dolores Quintana: We have no idea what the future is after our life on Earth. We don’t know.

Andy Brown: Well, if she is somehow able to see all this, I just hope she’s delighted, as she should be.

Dolores Quintana: Is there anything that you discovered about her either as a person or musician that surprised even you?

Andy Brown: I’d say that she personally told the truth about pretty much everything and things that seemed like they were tall tales; they all checked out when we researched them. She told that story in the Rolling Stone interview about how her first husband died going over the Kern River Rapids on LSD, on a rubber raft. We could never confirm that, and the film was almost done. Sure enough, one day, it appeared on newspapers.com. The story of that man, and it was him who had died. Even that, she was telling the truth. She didn’t like lies and that included about herself as well. She was her own harshest critic in many ways. So that, to me, was revelatory.

Dolores Quintana: Thank you. Brian, was there anything that was surprising to you?

Brian Lindstrom: Well, just her resilience. She kept writing right up until three days before her death. She really was true to her muse and kept faith with her music right up to the very end.

Dolores Quintana: Wow.

Andy Brown: Also, she was a pretty positive person who didn’t want to die. She was terrified of dying of an O.D. She just had a disease.

Brian Lindstrom: One quick story. You know, you can’t fit everything into a 90-minute film, so you have to let some things go, but for some reason, this story popped into my head, so I thought I’d share it with you. I was told by Art Johnson, a really talented guitarist and a dear friend of Judy’s, that one day, they were going to a street fair in LA on a Sunday.

They came across these two men in a brutal fistfight. Judy walked up to them and just started screaming at them. Today is the Lord’s day; you cannot be doing this and she stopped the fight.

Dolores Quintana: Just like that.

Brian Lindstrom: Just like that. None of the men in the group were willing to kind of step in and intervene. But she just said, today is the Lord’s day; you can’t be doing this. She had the kind of courage and conviction to pull something like that off.

Dolores Quintana: She really seems to have something that is just different about her. I think the cliched thing would be to say, oh, there’s something special about her. But there’s something that, even if you just look at pictures of her, there’s something that’s just different about her. Maybe it’s that truth-telling because, unfortunately, I think that a lot of people in the world have difficulty with that kind of truth.

Andy Brown: It probably affected her ability to be successful because she didn’t know how to play the game in the correct way that a woman pop star was supposed to. One other thing that we shouldn’t forget is that she was gifted with a great ear. She was born with that. She had perfect pitch. So there was a talent there that was pretty unique as well, and that, combined with all these other things, helped her create what we’re enjoying now.

Dolores Quintana: There seems to be a certain type of person who is fated to be a musician, no matter how hard it is for them. I’ve started to notice that they do have a perfect pitch, and it’s a quality that I don’t even think is valued as much now as it should be.

Andy Brown: Yes, it’s a quality of hearing. It’s like how a dog can smell more than we can. Their senses are activated on a higher level than most people’s senses.

Dolores Quintana: I agree. People like that; they hear things that we don’t hear.

Brian Lindstrom: Yeah.

Dolores Quintana: It’s frustrating for them as well when people can’t perceive all that they put into their music.

Brian Lindstrom: Absolutely.

Andy Brown: It’s a form of synesthesia, isn’t it?

Brian Lindstrom: Judy was at such a high level that even accomplished musicians, Jim Pons of the Turtles, who was also a bass player, Judy played bass a lot as well. As he says in the film, she wrote a bass part that he couldn’t—as he put it—he couldn’t achieve. So she had to play it because she knew exactly how it should go. I mean, she was that advanced.

Andy Brown: Right. She learned how to do it herself by watching her second husband orchestrate her first album. So she could write out all the charts for all those stringed instruments and horns and then conduct the orchestra on her second album. I mean, that’s not typical of pop singers.

Brian Lindstrom: Also, when Russ Giguere of The Association made his first solo album, he covered Ridge Rider, and the studio guitarist, I mean, who was a top-of-the-line LA studio guitarist, couldn’t play the part the way it was written. So they had to have Judy come in and play it.

Dolores Quintana: That level of natural talent that I think is indicated by having that kind of ear.

Brian Lindstrom: She could play so many instruments, including wind instruments. She could really do anything.

Dolores Quintana: Do you know how many instruments she could play? Or was it one of those things where she could pretty much pick up any type of instrument and work with it?

Andy Brown: She was adept at guitar, piano, and stand-up bass and was a bebop jazz bassist in clubs in the late 1960s. She also played the flute and clarinet and probably a lot of other things that we’ll never know.

Dolores Quintana: Anton Newcombe of the Brian Jonestown Massacre; I think he can pretty much play anything he picks up, and he also has perfect pitch. Do you think that maybe she had problems, say, with the people at the label and other people in music because her level of ability and her absolute conviction that truthfulness was the way led to issues with other people who didn’t understand why she was like that?

Andy Brown: Yep, and in that day and age, for a woman to be that way was also going to create some problems. Yes, no question, it was very hard for her to play that game. That had to do with her lack of a filter, maybe to some degree. But that was also part of what made her work so great: that she was not afraid to go and be truthful.

Brian Lindstrom: Yeah, I mean, if you feel like you are put on this earth to share this music, and then you have to go and open for the popular rock group of the moment in a hockey rink, it’s going to be a hard thing to be okay with and to kind of navigate.

Dolores Quintana: Or perhaps maybe when someone who really doesn’t have your talent, or maybe has never written songs before, is trying to tell you why your music doesn’t work.

Andy Brown: It was very frustrating for her, no question. J.D. Souther said that she had a pretty high opinion and estimation of her talents. He was not criticizing her; he was saying that she was correct.

Dolores Quintana: That’s the tragic thing. I think that people like Judee Sill feel like they’re not understood, and they don’t really understand why they behave the way they do. It’s because they’re trying to protect their art; it’s not so much about their ego. It’s more that it’s something that’s so incredibly important to them that they’ll fight for it.

Andy Brown: Creating in that realm puts them in a very vulnerable position psychologically and emotionally, and maintaining a sort of psychic health while doing that is not easy. I’m amazed at Adrianne Lenker because talk about making oneself vulnerable to one’s muse. She does, but yet she’s just one of the most solid and inspiring people I’ve ever met.

Brian Lindstrom: It’s like what Jim Pons says in the film about Judee. She felt like she was downloading it from a higher source, and it had to be perfect.

Andy Brown: There’s a lot of pressure.

Dolores Quintana: I think with that type of person, they put the most pressure on themselves.

If there’s anything that you would like people who watch the film to know or maybe something that you would like to impart to them about Judee or her work, what would that be?

Andy Brown: That there is a way to persevere through suffering and there are tools available to help people heal themselves that perhaps Judy was not able to avail herself of, in those days, because recovery was not something that people talked about then and PTSD wasn’t, but that there is hope. I find inspiration in her strength in that regard, despite the fact that she herself didn’t make it, but she had a disease, and it was more powerful than her. So I think that’s what I would say.

Brian Lindstrom: I would kind of echo that and just quote the last lyric Judy sings in the film, “However we are as okay.” Our task here on Earth, I think, is to understand our suffering and transcend it. Judy, I think it was all about transcendence; all of her songs, all of her writings, she really longed for it. I would argue that she occasionally reached it in her music and was brave enough and selfless enough to share it with us.